DEAN CROSS

SOME THINGS TO THROW AWAY

Bus Projects, Melbourne / Naarm

6 May - 9 July 2022

Installation view, Dean Cross, curated by Sarah Hibbs, “some things to throw away”, Bus Projects

‘some things to throw away’ is a new exhibition presenting thoughts on value, transaction, scale and function. I have moved through so many iterations of what this exhibition could be; each time the space between content, subject and realized form becoming narrower and narrower. The labour for this exhibition began in August of 2019 when I submitted my application to exhibit at Bus. The idea I submitted was centred on establishing an unofficial auxiliary branch of the Victorian Woodworkers Association, and turn wooden bowls in the gallery. Needless to say, that it is not happening anymore. That idea has since morphed and found its way into other exhibitions in other parts of the world. Then, through the fog of covid, I forgot about the exhibition completely until recently when I was reminded that the opening night rapidly approaches. So, I had to think fast – something deliverable in a short amount of time that still is rich with content and elegant in its presentation (a revealing glimpse into the priorities of my practice). I wanted to give away 100 litres of petrol under the title of Free Fuel, but that became unmanageable and ultimately unsafe. So now I give you something to throw away.

- Dean Cross, 2022

Installation view, Dean Cross, curated by Sarah Hibbs, “some things to throw away”, Bus Projects

Photographer: Christo Crocker.

Scarcity is a basic tenet of economics and creates its most fundamental problem – resources are finite, and the earth does not contain enough to satisfy unlimited human demand. The allocation of these finite resources is driven both by human action, the systemic framework of laws, cultural norms, and hierarchies [1] in which they act. In this intense election year, questions of power and governmental authority are at the forefront of our collective consciousness.

For Dean Cross’ first solo exhibition in Naarm/Melbourne, ‘some things to throw away’ functions as an ascetic assemblage of found object and text. An exercise in paratactical [2] aesthetic simplicity, its sparseness references the omnipresent scarcity of the resources around us. ‘some things to throw away’ gestures towards the inherited bureaucracies and power structures within which we all find ourselves.

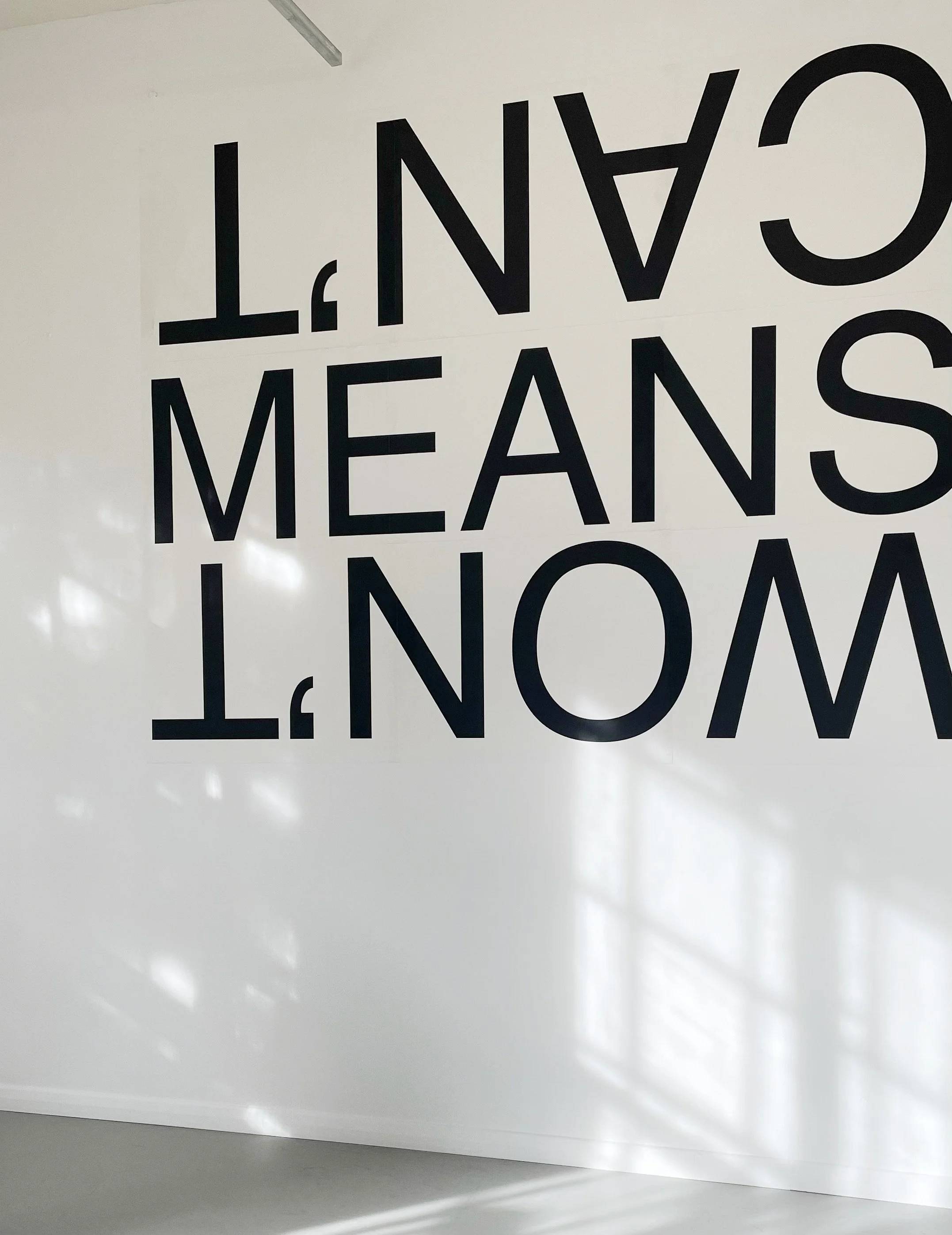

Cross’ bold declaration WON'T MEANS CAN'T (2022) is a linguistic truism, where form becomes an integral element to content delivery. By flipping the oversized sans serif text, the abstraction of signifiers makes their meaning more salient - as we stop to decipher, we also stop to think, and not merely mindlessly consume. The artist becomes choreographer[3], using his own hand to guide the neck of the audience to pause and consider who won’t, who can’t? And why? Do they simply lack resources, or is this a broader symptom of what contemporary society (or at least for those with power), believes to be valuable?

As a counterpoint to the large-scale text, a small object hooked on the adjacent wall draws us in for closer inspection. Here sits the readymade Lure (2022): an iridescent fishing lure, unassuming in its potency. The object is strange and rather beautiful, but also functional. For some, it’s a tool for leisure or socialisation, for others, for labour and a source of sustenance. Made of primary plastic – a petroleum-based polymer, to be specific – that has been processed from crude oil, it is not derived from dinosaurs[4] but rather, from ancient aquatic phytoplankton and zooplankton. A simulacrum of nature, this fish-shaped lure is a fish stick of sorts, made of processed, homogenised sea life, and designed to be highly appetising to its target market. [5]

To trace the origins of this plastic-cum-fishstick, we have to look back approximately 250 - 500 million years ago [6], when the continental shelves of Neo-Tethys, Gondwana [7] experienced seismic tectonic shifts breaking up the supercontinent. The rift basins were perfect incubators of life. Shallow and warm, sea life thrived, and the oceans became rich with bio-diverse marine life; algae, plankton, plants and small sea creatures. As the flora and fauna completed their life cycle, the organic matter settled on the ocean floor, mixing with other sediments. Over millennia, this organic-rich sediment turned into vast underground reservoirs of crude oil, which, arguably, have been the engine driving our global economy since the industrial revolution.

Today, Australia imports almost all its oil; 51-53% of our imported refined petrol comes from Singapore’s refineries, with 18% from South Korea, 12% from Japan.[8] Over two-thirds of Singapore's crude oil imports come from the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait [9] – countries who form part of the Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) [10], and who have access to the world’s largest oil reserves. It should be noted that some of the world’s largest oil producers, including Russia, China, and the United States, are not members of OPEC, which leaves them free to pursue their own objectives. [11]

Australian industry can’t [12] compete with cheap labour offered offshore. Production of most goods has decreased over the last half century, and most of our primary plastic and primary plastic products are now produced in China. It’s probable that this particular lure was produced there, and imported into the country, to be purchased by Cross and now fixed to the wall of this gallery, located in Melbourne/Naarm. At the end of this exhibition, both lure and wall text will be discarded. Unable to be easily recycled, they will likely end up in landfill, and the only relics of “some things to throw away” will be archival documentation. [13]

This humble fishing lure is a globally distributed, mass-produced instantiation of a tool that eclipses geographic borders, temporal eras, social hierarchies, and cultures, and the motivations that propel people to cast these fishing lures into the water are varied. [14] In Australia, fishing transcends class. The wealthy may fish from their large gleaming yachts, for leisure, for sport, for bragging rights, for company, and for food. The precariat, working, and middle classes won’t [15] have the same gilded platforms, but nevertheless seek the same prizes from tinnies and shorelines. For thousands of years, fishing has provided socialisation and sustenance, and continues to do so.

Dean Cross, I will never back flip again, 2020-22, printed ink on wall paper, 227 x 295 cm

When permitted, that is. It should be noted that currently almost all Australian states require a licence by the State Government. In NSW, where Cross is a current resident and does most of his fishing, one of the listed exemptions from holding such a licence falls under the cultural regulations act; “Fishers who are Aboriginal persons are exempt from paying a fishing fee.” [16]

“One small win I suppose. But the real complications arise when the representative from Fisheries NSW asks to see my licence to which I reply 'I am Indigenous' - my white passing posing a real conundrum. Does the fisheries inspector believe me and potentially have one done over him, or does he ask to see proof and potentially come off racist…” [17]

The object could be considered portraiture - indeed, an out-of-office email from Cross about this exhibition returns the line ‘Gone Fishin’’. [18] For many First Nations people living on the unceded lands of this country, fishing was - and remains to this day - a culturally significant activity. In an as-yet-unrealised work, Cross’ handwritten note ‘My grandfather never taught me to fish’ points to a personally felt generational disconnect, and the broader endemic displacement of indigenous peoples from Country. Fishing was one of the most important activities for the Worimi. The temperate east coast is a generous provider of shellfish, oysters and fish that live in the waterways. So then, what does it mean for Cross, a Worimi man born and raised on Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country, whose ancestors are Saltwater people, to employ such an object? Lure becomes a signifier of the complex and interwoven infrastructures that govern the lands and waters of today’s settler-colonial Australia.

This fluorescent pink plastic form of a nondescript species of fish, made from resources extracted from the earth’s crust, exported and then processed in Asia, brought to Gadigal/Sydney and then Naarm/Melbourne, soon to be discarded and buried again. With “some things to throw away”, Cross provides subtle yet incisive critique. He questions the contemporary power systems in which we operate, from the macro to the micro, and within the context of intersecting geological, sociological, ecological, and political histories. Ultimately, this only leaves us with the unanswered, who won’t, who can’t? And why?

- Sarah Hibbs, 2022

FOOTNOTES

[1] Both explicit and implicit.

[2] Cross’ own linguistic invention, he explains: “It's an expansion of ‘parataxis’, which is a sentence that still makes sense when you pull bits out of it.”

[3] Cross’ background in dance has specifically informed his approach to exhibition-making. “When you make a dance, it often starts with a gesture, a waving of the hand. It has no inherent meaning, but once you add in another gesture, a nodding of the head, you develop a relationship.”

[4] This common misconception was started by the US-based Sinclair Oil Corporation as a marketing tool in the 1930s, who then employed a green Brontosaurus as their friendly mascot in perhaps the least self-aware corporate self-description of all time. Dinosaurs were in fact too big, in the wrong geographic location, and in the wrong geologic time period.

[5] Similar to the way that frozen chicken nuggets can be purchased in the form of rudimentary dinosaur shapes – dinosaurs being the evolutionary predecessor of modern-day farm chicken (Gallus domesticus, the domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl).

Dino nugs | And Yet a Trace of the True Self Exists in the False Self / Circle of Life. Know Your Meme, <https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1961549-and-yet-a-trace-of-the-true-self-exists-in-the-false-self-circle-of-life>.

[6] During the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic Eras - from the Greek Palaio meaning "old", Meso meaning “middle”, Zoic meaning “life”, and Era meaning “era”.

Sorkhabi, R., 2010. Geoscience & Technology Explained. Why So Much Oil in the Middle East?, 7(1), pp.20-26.

[7] Now referred to by the imprecise colonial term The Middle East. “... the term first appeared in the mid-nineteenth century as part of the Europe-centered division of the East into the Near, Middle and Far East.”

Ibid.

[8] Richardson, Anthony. “Australia Imports Almost All of Its Oil, and There Are Pitfalls All over the Globe.” The Conversation, RMIT University, 24 May 2018. <https://theconversation.com/australia-imports-almost-all-of-its-oil-and-there-are-pitfalls-all-over-the-globe-97070>.

[9] U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Singapore International Analysis, August 2021. <https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/SGP>.

[10] Full list of the 13 countries includes: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela (the five founders), plus Algeria, Angola, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates. Qatar decided to leave the organisation in late 2018.

Member Countries. OPEC. <https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm>.

[11] Hayes, Adam. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Investopedia, Dotdash Meredith, July 2021. <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/opec.asp>.

[12] Won’t.

[13] Potentially including digital and/or physical copies of this very text. The majority of print copies of this text will be discarded and thrown away - hopefully, recycled. That’s on you, though.

[14] This doesn’t take into consideration commercial fishing, which has all sorts of far-reaching ecological and environmental implications and raises many questions about sustainability and how to best care for our earth’s natural resources.

[15] Can’t.

[16] Department of Primary Industries. Cultural fishing. <https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/aboriginal-fishing/cultural-fishing>.

[17] Cross, D. Google Docs comment from discussion about this very text, 2022.

[18] Cross, D. Gone Fishin' Re: Too much admin too many emails x, auto-response email to Sarah Hibbs, 25 April 2022.